Go-Far 2018: Eye on Estonia

AI's legal status up for debate

With the surge in self-driving vehicles, some believe robots should be held accountable for their actions

By Sean Loo

Pepper is Dr Karl Kruusamäe’s model student – an expert at the Estonian language, he works tirelessly on projects and assignments.

He has even worked at the headquarters of telecommunications company Telia as a reception officer.

But unlike his fellow students, Pepper has no rights. And while he will never graduate and get a degree, his legal status may soon change if Estonian lawmakers have their way.

Pepper is a humanoid robot developed by Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, and is currently under the supervision of Dr Kruusamäe, an associate professor in Robotics Engineering at the University of Tartu’s Institute of Technology.

Since 2017, Estonia has been working on redefining the legal status of artificial intelligence (AI) actors in disputes, giving them legal personhood. This is due to the increase in self- driving vehicles and the possible ethical and legal implications.

Authorities are concerned about the recent surge in self-driving vehicles and have sought to recognise AI as an entity that can be held accountable by law. The “general algorithmic liability law” would be a general law covering the legalisation of AI technology.

Self-driving cars are just “robots on wheels”. They are similar to drones and autonomous devices such as self-driving ships and our smartphones. This is why their decision-making algorithms share many similarities.

While “sectoral-based regulation” is cumbersome, an all-encompassing law could address the issue, said National Digital Adviser Marten Kaevats.

The proposal under consideration is also known as the “Kratt law”, added Mr Kaevats. The Estonian legislators have studied laws regarding self-driving cars since 2016.

In Estonian mythology, “Kratt” is a mythical slave formed from hay and household objects. It comes to life when its master makes an offering of three droplets of blood, sealing a pact with the devil.

While Kratt would do everything its master ordered, it had to keep working or it would become dangerous – threatening its master’s life.

“It is exactly the same as artificial intelligence,” Mr Kaevats said.

“AI systems are not linear systems. In a programme such as Microsoft word, when you press the ‘Enter’ key, the cursor goes one line down. In machine learning systems, it does not work this way.”

Mr Kaevats explained that complex AI systems rely on algorithms that react to situations with no fixed rulebook. The system only knows the statistical likelihood of an event happening, but another outcome could take place.

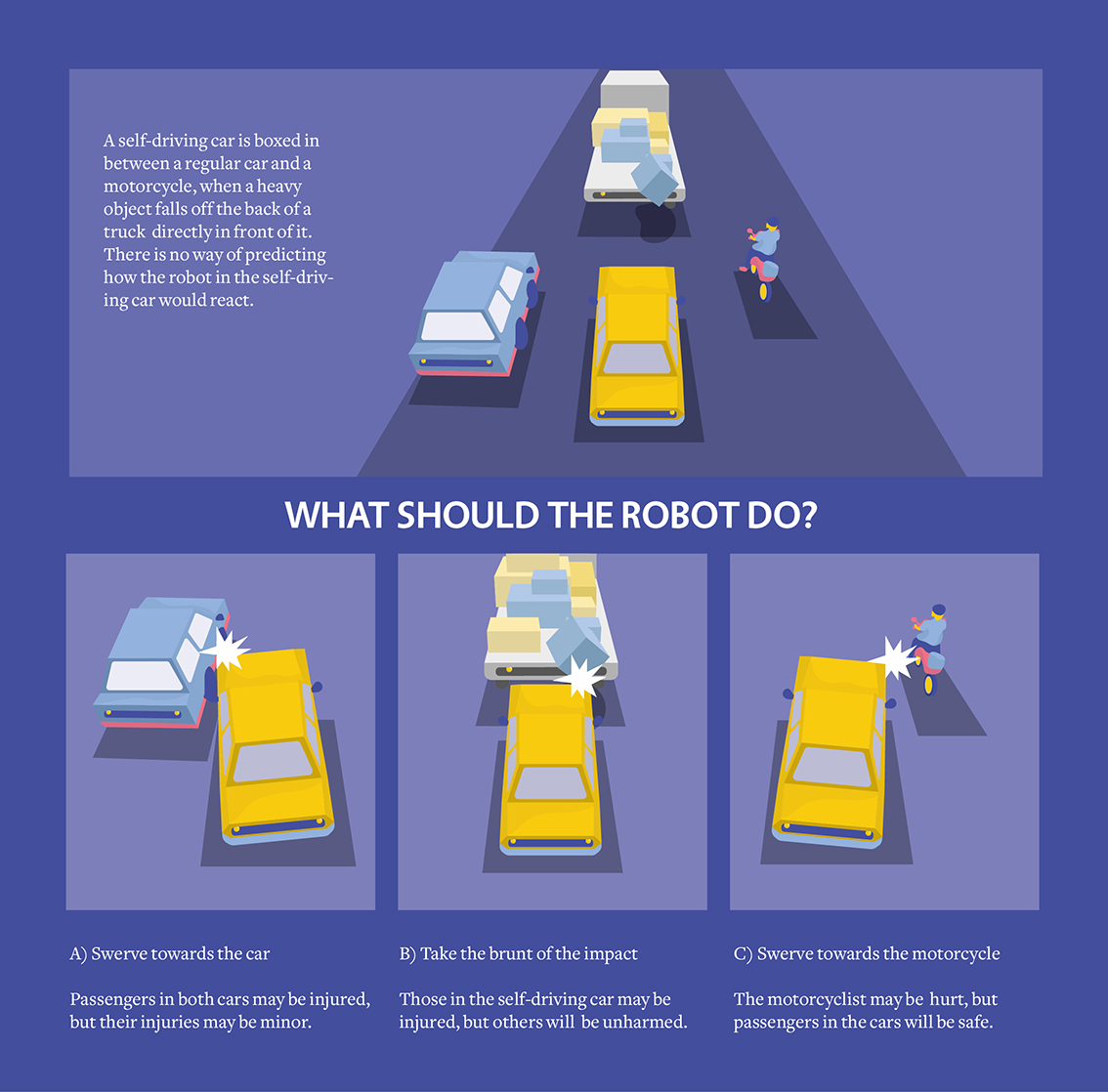

For example, if a self-driving car were to be boxed in between another car and a motorcycle, and a large heavy object were to suddenly fall off from the back of a truck travelling directly in front of the self-driving car, there is no fixed way of predicting how the AI would react.

The AI would have to make a split second decision to take the full brunt of the impact, or swerve towards to either the motorcycle or car — which might injure others — to minimise the passengers’ injury.

The legal status of AI would resemble that of a company, said Mr Kaevats. AI, would then be seen as a single entity, enjoy limited liability and separate from its stakeholders.

“A company is an extraction of the mind because if you’re a private citizen, and you make a company, then you can take a bit of liability from you and transfer that to a company,” Mr Kaevats said, adding that ultimately the owner-creator could still be traced and held responsible.

The government has been consulting the public in an effort to understand concerns about AI technology. This is because the question of who is at fault is often emotionally charged.

Mr Kaevats noted that the main concern of the public is the issue of accepting that in some instances, there is no one to blame.

“It’s important to have the whole society on board with this question,” Mr Kaevats added.

Deciding who to blame for an accident is a dilemma. Citing the example of self-driving vehicles, Mr Kaevats said: “If your child were to die in a traffic accident by self-driving cars, you definitely would want somebody to be guilty – emotionally it’s difficult.”

But at one point, there will be algorithms that will start to develop their own code, thus complicating the questions on liability, he added.

For Mr Kaevats, the proposed law would not rid manufacturers of liability, but rather, pinpoint the flaws in the decision-making algorithm of the AI in order ensure that it is improved.

A European Parliament proposal to give robots legal status met fierce opposition in January last year, with over 150 international experts signing an open letter to object the draft legislation.

In Singapore, Dr Zhang Jie, an Associate Professor at Nanyang Technological University’s School of Computer Science and Engineering, feels that the law “should be applied the same way” in the event of an accident.

Singapore has allowed autonomous vehicle trials on public roads since early 2017.

“Even though they (the AI) developed their own code, it is still pre-designed by the manufacturer,” said Dr Zhang. “I don’t think it has reached the stage where an AI could do things from its own free will yet.”

Tallinn based entrepreneur Sander Gansen says the implementation of Kratt law could prove tricky.

“While the law can be really nice on paper, in reality, it’s different in many cases,” said Mr Gansen, the Chairman of Robotex – a global robotics education network that organises the world’s biggest robotics festival held in Tallinn.

The 24-year-old used bicycle laws as an example, pointing out that there are laws prohibiting cyclists from going against the flow of traffic on the roads.

“In such a situation, by law, if a car were to hit the bicycle, it should be the cyclist’s fault. However, in reality, most of the time the car would be found to be at fault because it is bigger,” Mr Gansen added.

For self-driving cars, this would mean that the AI could still bear responsibility regardless of the circumstances of an accident involving a pedestrian, cyclist or motorcyclist simply because the other party is deemed to be more vulnerable.

Like Dr Zhang, Mr Gansen believes that there is currently no AI system capable of learning by itself. However, Mr Gansen supports the development of such a law.

“It is a good thing that the government is already thinking about the implications to society even before the arrival of such technology, thus we’ll immediately be ready when such technology comes,” he explained.

The Kratt law is still a work in progress and implementation will be a “long process”, said Dr Kruusamäe.

“With AI, there are still so many unanswered questions and we haven’t even started fully writing down what it should be about,” he said.

Mr Kaevats said the taskforce looking into the law will present their findings and recommendations to the Estonian Parliament in May next year.

“We will then enter into the second phase of the public debate. I’m an optimist, but I hope to be ready with that law by the end of 2019, or perhaps in the beginning of 2020,” Mr Kaevats said.